Note: This has been cross-posted over from the following: https://questqyubey.substack.com/publish/post/142565699

Tell me if you’ve heard one of these before:

“Combat is the worst part of this game. Can we skip it?”

“How do I keep my players attention when it’s not their turn? They just zone out.”

“My players just keep doing the same thing over and over again. It’s not any fun!”

In a hobby where a great majority of our time is spent making imaginary people fight, it might come as no surprise that these questions appear frequently but it always interested me. Whether running an established game or experimenting with something homebrew, there often arises the question: “How can I make this more interesting or fun for the players?”

Lines in the Sand

Before we jump in, I’d to set some ground rules for definitions; particularly around “Fun” and “Interesting”, since that can get quite subjective. I’ll be relying on the ‘Agency Theory of Fun’ for this piece, which you can read more about here:

Where it’s defined as, quote,

“the great enjoyment elicited by tabletop RPGs (and some videogames) is a result of creating a sense of agency among their players.”

This has mostly been my experience playing and running games and I find it a very useful yardstick to design for. Agency, or choice, generally leads to fun so the more it can be supported and empowered the more fun should ensue.

But not all choices in games are made equal… or interesting.

In a game of Rock-Paper-Scissors (or whatever regional variant you know that is obviously wrong) there are three possible choices to make in any round, but there is effectively no difference between them. You can infer that Rock will be more likely to succeed if your opponent usually choses Scissors but that knowledge is not part of the rules. Without context, there is no meaningful decision to be made for one move over another.

In the board game Candy Land the player may move 1-to-6 spaces on each roll of the die. The players cannot affect the result of the die and so movement is entirely random. A player's skill or analysis of the game situation has no bearing on their chances of success.

The ‘Quantum Ogre’ from Hack’n’Slash blog illustrates an example where the players may choose two different destinations, but the result is always the same: you always fight the Ogre the GM has prepared. In this case, reality itself warps to ensure the decision made always has the same consequences.

See: https://hackslashmaster.blogspot.com/2011/09/on-how-illusion-can-rob-your-game-of.html

These are examples of what I would call “meaningless” choices: ones where the player’s thought process is disconnected from action or consequences. A meaningful choice should be informed and have impact; it must have agency and intent. Without that, there is no strategy and, by our metric, less fun to be had. Now, a meaningless choice can still be entertaining, especially when narrated well by a skilled GM, but I consider narration to be outside the purview of Agency Theory and it won’t be considered here. To me, good narration merely covers up problems rather than fixing the root issue, which is what we’ll be analyzing.

Problems: Optimization, Automation, and lack of Choice

As stated earlier, “making combat interesting” appears to be one of the common questions and categories of advice you might see online in the TTRPG space. Dungeons & Dragons 5th Edition in particular seems to have a reputation for being slow to run or boring to play. I've collated a few random examples from the web for comments:

There’s a concept in MMOs and video games of a “Macro”;

“a series of predefined commands or actions that can be executed with a single keypress or button.”

See: https://thegamingmecca.com/what-are-macros-in-gaming-and-how-do-i-set-the/

These exist because people wish to automate complex sequences of actions and streamline their play. With macros, you can perform multiple tasks or combinations of moves with just one input, giving you a vital competitive edge. It’s worth noting macros are not typically changed on-the-fly, they’re pre-determined. They also do not stop you from executing those actions manually, just automate the inputs you would have been doing already.

This appears to happen in TTRPGs as well when people refer to getting bored of only taking the most ‘optimal’ actions: always lay down oil, throw fire, and trip anyone that escapes. If the answer to a given situation can be the same every time, we shouldn’t be surprised if people start automating their way to that answer. Sometimes this can be called "optimizing the fun out of the game" or "solving" it akin to a puzzle. However, this should not be as prevalent as it is if every combat required different answers to solve. What this tells me is that the combat these people are having can be answered in the same way each time.

You could consider an optimized routine to become a player's "default action". Justin Alexander defines a "default action" as:

(1) A default action is basically something that a character can do to trigger interesting content even if they have nothing else to do.

See: https://thealexandrian.net/wordpress/38659/roleplaying-games/open-table-manifesto-part-2-what-an-open-table-needs

(2) A default action. If a player is standing in a room and there’s nothing interesting to do in the room, then they should pick an exit and go to the next room.

See: https://thealexandrian.net/wordpress/15140/roleplaying-games/game-structures-part-3-dungeoncrawl

Both of these definitions use the word 'interesting' to the same effect: the situation is passive and a default action will trigger content. I don't think it's a perfect explanation as it doesn't cover situations where a situation is already interesting or demanding yet there is still an obvious or optimal action to perform. Still, the term is useful when referring to "the optimal, obvious, or strictly-best choice to be made for a given situation."

If you want to add to something, you must first agree on what the desired end goal even is. Is it narrative immersion? Is it to challenge player skill? Once this is no longer agreed upon, the only possible innovation with broad appeal is to reduce complexity, and thereby increase ease of use.

See: https://princeofnothingblogs.wordpress.com/2024/01/01/on-design-and-anti-design/

If a player’s goal is simply to win the fight and defeat the enemies, it’s hard to fault them for finding the cheapest, quickest, safest way to accomplish that! It may not be interesting or fun, but those aren’t goals in and of themselves. They only become goals if the player becomes bored enough to not care about winning as much as they want variety. That desire becomes a goal.

I believe a lot of these issues have a similar root problem: a lack of consequences, agency, and discovery. Without consequences, why not do the same thing every time? It doesn’t change anything. Without agency, why bother caring about the consequences? They were going to happen anyway. And lastly, if given perfect information, why not make the strictly-best choice? That’s usually called “good play”!

To solve the problem, we either have to change the situation or change the goals. And to do that, we have to know what tools we have to work with.

The Dimensions of Combat

A big thanks to Arbrethil for the name here. I was gonna go with “Primitives” of combat but that sounds more like fighting cave-men. Dimensions is much more flashy.

This is the heart of the problem I want to examine.

What are the trappings of combat that inform decision-making?

What options do players and DMs have to establish and define a combat encounter?

What variables are actually worth keeping track of and how can they alter choice?

What drives player behaviour? What goals do they implicitly have?

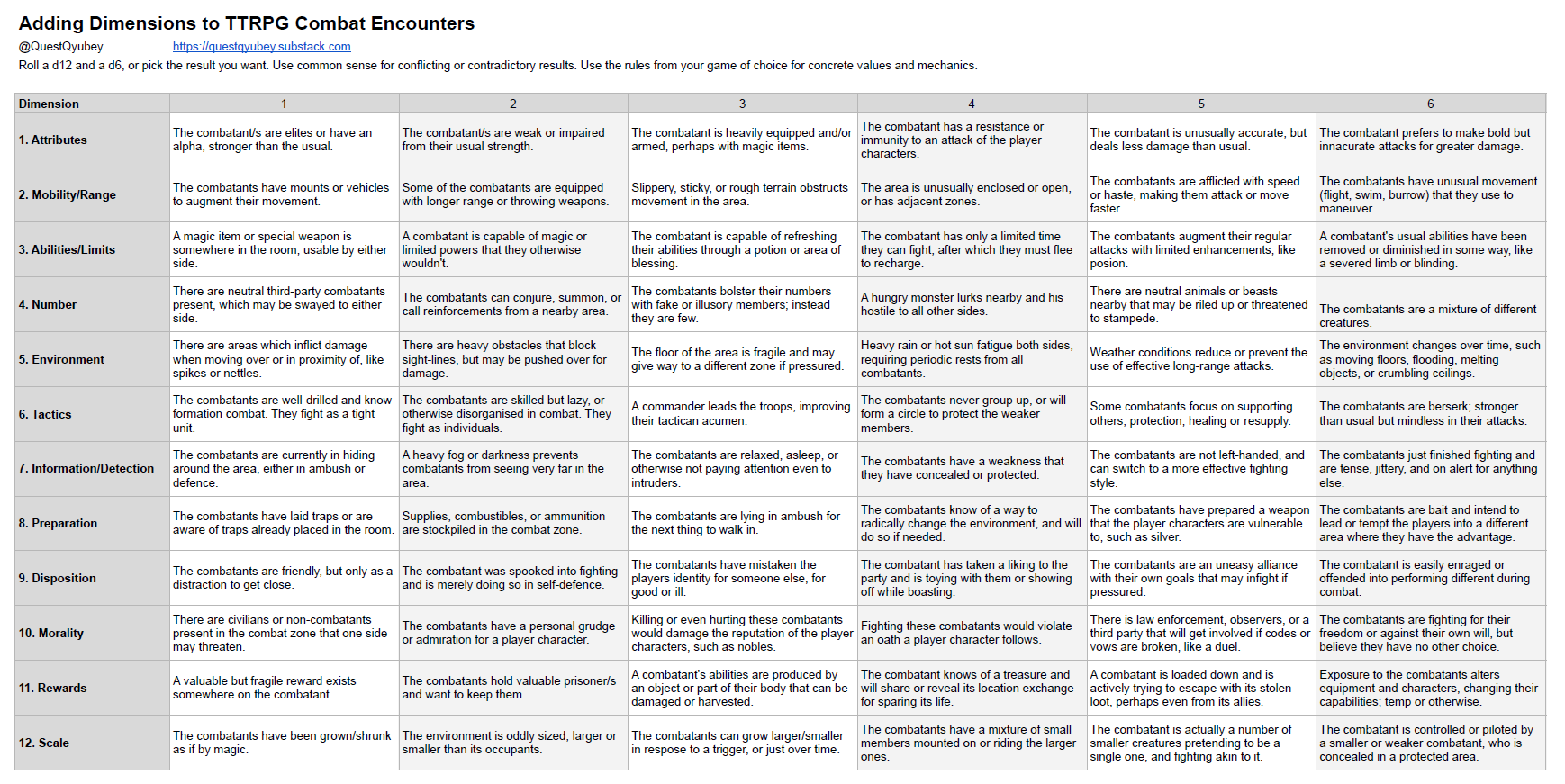

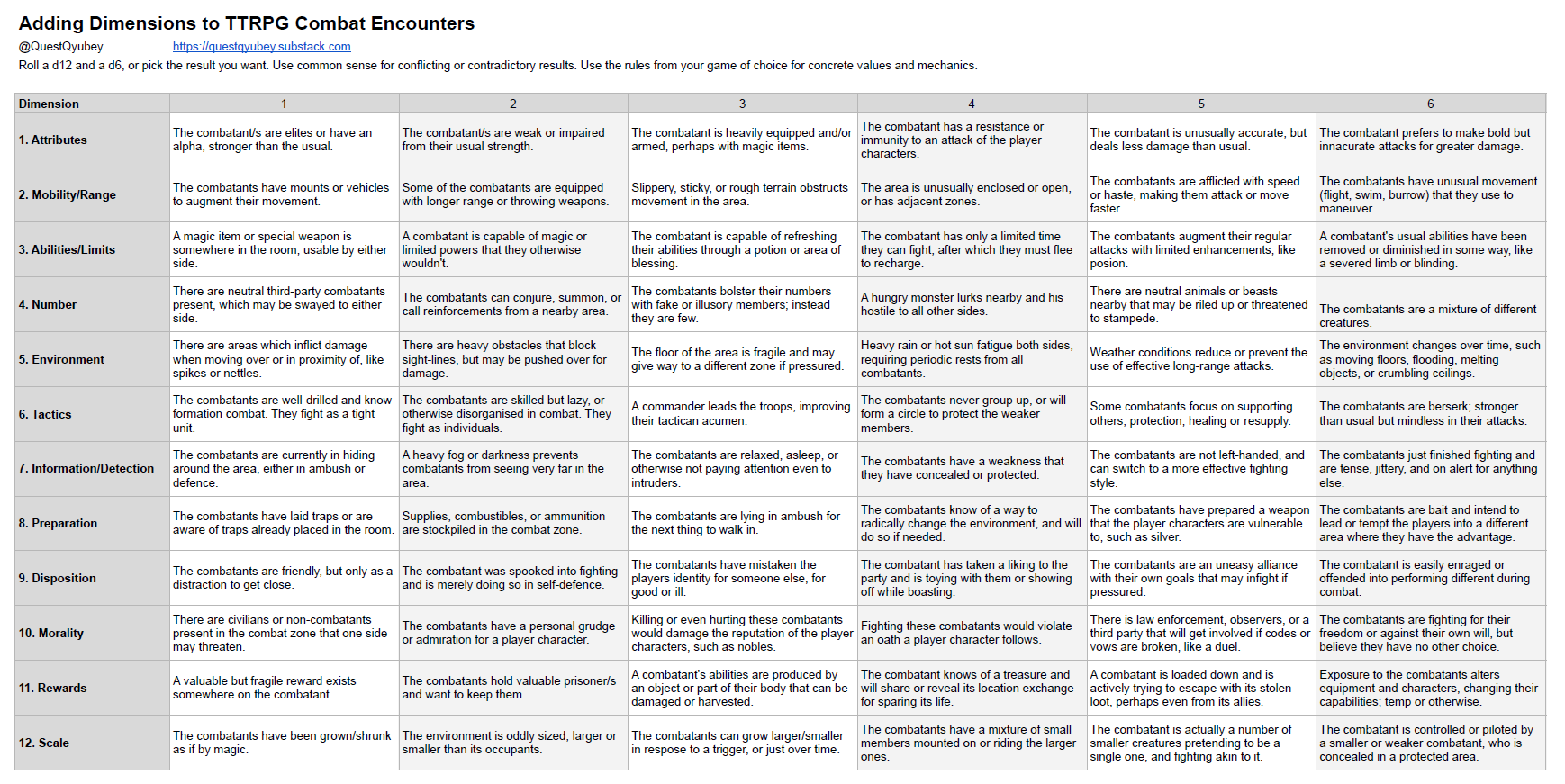

From hereon I'll be referring to such variables as the "dimensions" of combat. Additionally, our goal will be to produce something useful: a table that can be consulted to add more dimensions into combat. I doubt it will be all-encompassing but I hope to provide to combat what town and NPC generators do when developing a setting.

For our purposes I will be making a few assumptions:

I will be restricting the scope to traditional, turn-based, wargame-inspired TTRPG combat, though the concept should apply to many kinds of conflict. Anyone who knows D&D and its ilk should be familiar: turn order, attack rolls, hit points, etc.

To illustrate examples, we will define our seed fight as being a mirror-match of two identical human fighters in a featureless arena, intent on defeating one another. Their attributes and their equipment are identical, so the only variables that change are which one goes first and whether or not they hit and deal damage on a given turn.

Their default action is to make an attack roll and deal damage to the other. The results of their fight should be equivalent to a coin-flip, a 50-50 for either one winning.

Their goal is kill one another, and thus claim victory in combat. The over-arching reason for doing this is not defined.

This gives us a simple basis from which to iterate on and analyze whether our dimensions actually add anything of interest, and whether they are dependent on other dimensions also being present.

Using these assumptions, I believe I have identified 12 distinct dimensions for how the decision-making of combat may be affected; either due to a disruption of the default action, of new optional actions, or a changing of goals. I do not expect this is all possible dimensions of combat, but they are the ones that have occurred most prominently to me and friends in discussions. I’ve defined each with a naming category, a brief description, examples taken from various games, and a suggestion for how to implement it.

So without further ado:

1. Personal Attributes (Strong vs Weak)

The innate capabilities of the combatants, as related their default action.

This is a broad dimension as it covers everything from hit points, hit chance, damage, mitigation, immunity, buffs, debuffs, and their action economy. It does not include capabilities which add additional options, such as spells or powers, which are distinct enough to be their own dimension; and does not include capabilities which do not impact battle (lockpicking doesn’t matter in a brawl). A fighter with better capabilities is considered 'strictly-better' and stronger than the enemy quantitatively (2 is better than 1). This may not guarantee their success (especially if the capability is meaningless in context) but often comes with it.

Examples: Virtually every RPG out there includes these to some degree: the six attributes of D&D, the nine for the World of Darkness, the rings of Legend of the Five Rings, even the simple two-stat systems like Lasers and Feelings. Almost every RPG is built on some degree of personal differentiation between players and enemies. Unless you are creating a game from scratch, you will find always examples of innate attributes that affect default actions.

To deliver on this: simply play the game and enforce the rules that exist! More specifically, have a difference between fighters: Strong vs Weak, differing in health, chance of hitting, damage mitigation, amount of actions, etc. The value will only matter if it affects decision making: adding more damage onto a one-hit kill doesn’t change anything. Capabilities might be limited by frequency, uses, risk, or time if balance is desired.

2. Mobility & Range (melee, ranged, speed)

Whether a combatant can perform their desired action or must satisfy a condition in order to do so.

Many games differentiate between close combat (melee) and ranged on the basis of what is a valid distance to attack from. More still dive into exact measurements or 'range bands' to quantify this distance. Changing one's distance is usually a matter of moving on their turn up to whatever allowance is provided to the character. How far they can move may be modified based on the terrain (rough ground), their condition (tied up, slowed), or the medium of travel (walk speed, swim speed, flight speed). Whether they can attack may also have minimum and maximum ranges, thus making positioning a core concern.

Examples: Again, virtually any RPG will have these concepts; even low-tech RPGs that may not involve firearms will still have thrown weapons. D&D provides movement allowance per turn in feet/round and the distance on weapons is given in terms of normal and maximum range (which incurs a penalty). It also includes various movement types for different terrain such as walking, running, swimming, and flight. L5R includes Range Bands from 0 (touch, 1-2 feet) to 6 (sight, +100 yards), and ranged weapons list a minimum and maximum range the weapon can be used at, relative to the target. Sword World includes specific positions on the battlefield relative to allies and enemies; rear-guards for each side (where ranged weapons are fired from) and a shared frontline (where melee occurs).

To deliver on this: This dimension is easy to deliver but can be delivered in many ways. In games where positioning matters a lot (area attacks, flanking, formations) the distances will often be specific and discrete, whereas more action-based games will opt for simpler tracking, like simply stating if the target is close or far. The dimension will only matter if the area of combat in which it can be meaningfully used; if trapped in a 30ft room, high mobility will not matter as the enemy can always close the gap, and the dimension is moot. Terrain and obstacles strengthen the need for good positioning and can provide elements like cover, choke-points, and flanking.

3. Abilities & Limits (spells, ammo, fuel, powers)

Other actions and options available to combatants that are more limited or less conditionally valuable than the default action.

The actions a character can perform which are not the default action (eg, a standard attack), which often have higher impact and limitations. If the limits of an action never actually matter (eg, the spell has limited charges, but they can be refreshed out of combat easily or at no cost) then that action will become the player's default action - until something better comes along. Similarly, if the benefit provided is less than the default then the action is unlikely to ever be used, unless another dimension makes the benefit worthwhile (a weakness, positioning). Providing alternative actions to weigh against one another is one the simplest and strongest ways of providing choice.

Examples: D&D, particularly modern D&D, provides many examples in the form of spells, magic items, equipment, class powers and abilities. Exalted features Charms prominently that tie into many facets of the system. Superhero games like Marvel Super Heroes give Hero Points, which may be spent to perform Power Stunts outside of their usual capabilities. Capabilities such as Movement might also be limited by time or charges, such as a flight spell or a fueled vehicle.

To deliver on this: This is a rich dimension for design to play with, as it can interact with virtually any other part of the game to endless degrees. Care must be taken to avoid making a power into a new default action or making it useless, and a lot of work goes into this fine balance. This is usually where much of the power fantasy of games comes from; supernatural and exceptional capabilities beyond the norm, as defined by the Personal Attributes.

4. Number of Combatants (one to many, many to many)

The number of combatants per side that share the same goal or allegiance.

This is one of the most transformative dimensions in combat. By adding more combatants, there are more turns to take; more variety in personnel, more actions to synergize between. It provides more space for design to mix Strong and Weak enemies, to provide qualitative differences between actions, and enrich positioning and tactics. Combatants may be a homogenous mix (common for enemies) or a heterogenous mess (common for players), so long as their Personal Capabilities and Abilities remain meaningful to the relative scale of conflict. A third party can provide a dimension of possible allies, enemies, or a unaligned threat to both sides.

Examples: Classic D&D often assumed groups of 8 or more members while modern D&D assumes 4 players in a group. In Ars Magicka, the players may control multiple characters through rarely all at once (troupe gameplay). In mass battle and domain play, players may assume control of an entire army; separated out into controllable divisions or groups. And as for wargames, they live and breathe on numbers.

To deliver on this: This dimension is easy to introduce but, like Abilities, can be hard to balance. Two combatants have twice the attacks and health of one, which is why it’s typically best to have many Weak vs one Strong. Many RPGs get this dimension for free by the sheer fact of being multiplayer games, but you can see it reduced in certain situations as well. A thief who sneaks off alone, a wizard entering another plane, or a hacker diving into the web all become solo play in an otherwise multiplayer game, reducing this dimension for one side - but they will often still experience it as they encounter groups of enemies.

5. Environment (obstacles, terrain, weather, access to other zones)

The spatial mapping and attributes of the area to which the combat takes place in.

Like number, environment is highly transformative for the previous dimensions. Obstacles and terrain have endless uses and forms, from fortifications that block attacks, to massive chasms that require specialized movement to even cross. By preventing or modifying the effect of default actions, other actions may be re-evaluated and enriched. A mass amount of units forced into choke-point will lose much of their benefit in numbers. The environment may itself provide new actions, such as creating, destroying, or using obstacles and objects against the enemy (collapse a pillar on a foe). Environments can also link in unique ways; not just a door to the next room but a collapsing floor, a teleporter, or a transformation of the entire area into something new.

Environment could be split even further into ambient environment (weather, temperature, atmosphere) and tangible environment (obstacles, terrain).

Examples: War and strategy games provide the best examples for this. Many wargames feature terrain pieces; from cities and forests to individual buildings and obstacles. D&D and its ilk often use Battle-maps and Terrain Tiles to represent the space of a combat, while games like FATE codify the environment down into discrete Aspects which can be used by the players in creative ways.

To deliver on this: This dimension matters most when the environment meaningfully affects actions and strategy; terrain may block attacks, slow or prevent movement, inflict damage, conceal and protect, and so on. If it does not affect other dimensions, it is likely just set dressing and acts the same as narration. Terrain is most easily conveyed with a visual map or pieces (to convey spatial position), but defining it in terms of lists and locations is still sufficient. What's more, environment will determine whether fleeing is possible, or if the conflict can be taken to a different area entirely, where the active dimensions of combat may be entirely different, and hopefully more in the player's favor.

6. Tactics (coordination, formation, support)

The cooperation and coordination of combatants on a single goal or aim during combat.

Tactics and coordination are a force-multiplier for multiple combatants during combat. Pincer movements, flanking, ganging up, alternating strikes, and formations; dense or loose. The specifics and aims may differ based on situation and the capabilities of the combatants, but they all allow the many to act as one; towards a common goal. Implementation may vary based on the average intelligence of the group, or if they receive orders from a commander or instruction system, such as flags or signals. Disruption and removing of their source of information is a powerful means to not just break their advantage but to sow confusion and fear among the enemy.

Examples: Many monster manuals include information on how the creatures 'should' be played, according to their intelligence and nature. Wargames like 40K can codify these into ‘Strategems’ which can be activated, and Abilities which may be conditional based on certain positioning or relation to other combatants. Kingdom Death Monster and Gloomhaven feature "AI" decks of cards which dictate the decisions of the enemy in place of a GM.

To deliver on this: This dimension can be complex to implement but is rich in consequence. It requires the GM to have an understanding of the capabilities of each combatant, both in how they would best fight and how they should actually fight. Animals may prioritize food and safety over victory; berserkers may persist even against overwhelming odds; and armies may flee when they see their commander lost or their formations shattered. Players recruiting NPCs will learn quickly to assert their own tactics, and to undermine those of the enemy.

7. Detection & Information (surprise, stealth, visibility, weaknesses)

Whether combatants are aware of each other, their capabilities, and allegiances.

The fog of war is an important aspect of strategy games, and so too in TTRPGs. Stealth and surprise can allow for deadly first-strikes, but only if their presence is successfully concealed. Even if not actively hiding, visibility in weather and fog or across obstacles can just as easily conceal combatants and the terrain. A hidden chasm may be a deadly thing to miss. Information about the previous dimensions is paramount to making optimal choices, so discovering it may be as important as dealing damage. If an enemy has an immunity to the default action, its value will become nil until surpassed, and a new one must be found - and quick.

Examples: Many strategy games (Age of Empires, Starcraft) feature sight and fog of war, where the player can only know what is happening when their units have sight on it. D&D as well includes light sources and vision ranges when delving into the darkness, which can obscure enemies and traps. Many games feature stealth and sneaking skills which can act to obscure an enemy, and then trigger a surprise round of combat. Like Tactics, Information can be incredibly powerful. The "Stealth Archer" of Skyrim is famous for trivializing combat by allowing them to deal lethal damage before the fight even begins proper; eg, when both combatants are aware and capable of attacking each other.

To deliver on this: Surprise can be an incredible benefit, as can hiding a strength or weakness. It is best when the players are made aware of not only their ability to hide, but to search and discover as well. To learn or experiment with the unknown and build their knowledge, both inside a single encounter and across an entire world. Perfect, free information diminishes this dimension of combat and deprives players of perfect calculation, which helps when building tension and risk. It is important to remain fair when dealing with hidden information though, as there is great potential for abuse.

8. Preparation (traps, ambush, positioning, triggers)

Pre-planned actions, tactics, and elements established before the fight begins.

Dependent on Tactics and Information, plans and preparation can be highly valuable. The ability to ambush an enemy requires fore-knowledge and time to prepare, but can end a fight before it even begins. Traps may not be placed by a combatant either; a trapped hallway or dangerous swamp are simply elements of the environment but can be just as deadly. Preparation may even be as simple as the party waiting for their enemies to be in the perfect position for a limited strike, like an explosive, as an opening gambit.

Examples: D&D has Tucker's Kolbolds as an infamous example of incredibly prepared monsters who have traps, fortifications, and tactics ready to deal with would-be slayers. The individuals are weak but through combat dimensions they are a formidable force. To a lesser extent, building traps and bringing specific kinds of equipment may count as preparation, but do stretch the limits of a "combat dimension" as they primarily occur outside of combat. “The Monsters Know What they are Doing” is an entire book about the tactics of enemies and monsters alike.

To deliver on this: Preparation is often a natural thing that occurs when players are allowed to... well, prepare for encounters. As a combat dimension, it is dependent on other dimensions providing opportunity to act; traps to trigger, positions to take, weaknesses to exploit. As a GM, providing this is best in the form of allowing players some time to prepare, or giving the enemies their own in expectation of some event, like people busting down the door, and playing fair when players manage to circumvent them.

9. Disposition (morale, diplomacy, intimidation, cohesion)

The social disposition of combatants towards one another.

While most combat is going to involve people trying to kill each other, there's no reason they can't like each other. The fight may not be a personal affair, it may even be driven by passion or betrayal. Thieves and bandits may act affable or friendly as an opening act, or timid merchants may have simply opened fire out of fear and lack of information. Enemies that see combat going sour may decide to flee or beg for their lives, or accept bribery in exchange for sparing the lives of the players. Combat may not end in blood if a skilled defusal achieved or bargain can be struck. Enemies may even work together against a greater foe that enters the fray.

Examples: Classic D&D and OSR often feature Morale and disposition as a feature when dealing with enemies or hirelings. If it unknown whether the encountered party is hostile or not, the GM can roll for it and act accordingly. Exalted 3rd Edition has an entire sub-system for persuasion to convince people, although it isn't typically performed mid-combat. Many systems provide Diplomacy, Intimidation, Seduction, and Bribery skills to manipulate the enemy; and in the worst cases act as a light form of mind control.

To deliver on this: the GM must develop opinions for the enemy, a way to discern it, a way to affect it, and an idea of the consequences. If an enemy is hostile, can they be bribed and what with? If friendly, is it only out of a desire to get close for an ambush or to steal without drawing blood? Conversation might not seem like something to be done during battle, but intimidation and distraction are common tracks to get an enemy to do what you want. It is important to not allow people to simply talk at length though; treat it like other actions in combat, with its own time and cost, as it can be just as decisive when used well.

10. Morality (codes, laws, beliefs, values)

The social and personal contracts characters abide by in their actions.

Our seed fight is a simple duel-to-the-death, but what of mercy? Role-playing games expect players to embody roles, including the personality and codes of conduct that character believes in. This will drastically affect how they conduct themselves in combat and other situations. A noble paladin slays only the wicked, while a policemen works to enforce the rule of law. The setting may feature codes of conduct, regional laws, alignments, factional guidelines, with punishments and benefits for sticking to them. Even the personality of a character defines their expected conduct and can have great ramifications for play; fighting when hope is lost, or fleeing for selfish reasons.

Examples: D&D features both Alignment and the Oath of the Paladin, which expect certain conduct and behaviour from combatants. Vampire: The Masquerade has the titular Masquerade to uphold, which has dire consequences for breaking, inside of combat and out. Legend of the Five Rings features an Honor and Glory system that tracks the player's conduct as a samurai. Virtually every RPG also includes reflections of the real world with legal codes, rules of law, and religious doctrines - even if only NPCs care about them.

To deliver on this: This dimension occurs both outside of combat and within, so featuring it requires the code to matter during conflict. Killing people may defy a code of law and bring law enforcement into the fight, while a religious doctrine might prevent the use of bladed weapons or might even demand the player attack perceived evils. Player characters will often produce their own codes and preferences during play, such as protecting beloved NPCs or picking and choosing the laws they agree with. What’s important is to make sure players understand the consequences of an action and belief; even the ones they make for themselves.

11. Rewards (treasure, quests, upgrades, blessings)

The possibility of additional rewards in exchange for certain combat actions or limitations.

Defeating the enemy is the default goal for most combat but it is hardly the only driving factor. Experience and material rewards often come with slaying enemies, either as loot dropped or as payment from patrons. During combat however, further rewards may be provided for dealing with an enemy in a certain way. A bandit left alive may lead players to their stash of treasure, and hostages rescued may come with bonus rewards. Monsters may provide direct benefits if their bodies are left intact enough to salvage from, in the form of weapons and materials.

Examples: Monster Hunter as a series allows you to gain certain weapons by damaging the tail of an enemy enough to sever it, and Kingdom Death Monster allows much the same by using a monster's limbs as weapons. ACKS II provides a system of harvesting destroyed monsters with rewards based on how badly the monster was defeated; avoiding slashing and burning may result in a more intact and valuable pelt, while obliterating it utterly will destroy any components that might have been salvaged.

To deliver on this: This dimension is relatively minor but can be highly enticing, especially if the goal of combat was to collect resources. Notably, the reward must affect decision-making; it can’t simply be more treasure they get for defeating the enemy normally. The GM must be aware of the kinds of rewards the players would enjoy and how to inform them of how they can achieve them during combat. A failed or poor attempt can be a good way to let them learn what they should do next time to gain greater rewards (ruining a pelt or skin). If the players are on a task or quest, the limits may be made very obvious and bonuses provided for sticking to them. For that, it is important that the payer have some way to verify the players stuck to the goal or they are quite likely to try and cheat.

12. Scale (Small vs Large)

The substantial difference in capabilities between combatants that demands different actions and approaches.

David versus Goliath should be a more interesting fight than it is, but David did roll a crit. A man fighting a mountain is a wholly different endeavor to like versus like. Whether a combatant can hide in small crevices or tower over their enemies will affect virtually every facet of combat, beyond even the view of default actions and capabilities.

Examples: Shadow of the Colossus is a memorable example of a man-sized combatant slaying giant foes, only killable by very specific weaknesses. D&D often features a difference in personal attributes based on size, but ACKS provides more detailed rules for scale-different combatants to avoid being stopped until properly threatened, for clambering atop giant monsters, and even swallowing smaller combatants whole.

To deliver on this: This dimension is highly specific but can be quite transformative. The more extreme in size away from the typical human requires more consideration of what rules should apply and what changes from their POV. A tiny fairy might be able to hide in hundreds of places but be incapable of grappling a man. A giant is unlikely to be stopped by a single man and may treat impassable terrain as little more than speedbump. Often its best if there is some way for the scales to engage with one other, such as climbing or clambering on a larger foe or targeting specific weak points. As the larger combatant is usually an example of Strong, its best if their numbers are kept low when fighting relatively smaller enemies (swarms versus a man, armies versus a dragon).

Each of these dimensions, I think, occupies a particular niche and set of variables. Many are inter-related, such as Information and Preparation (which you could combine under an umbrella of “Information Asymmetry” to cover all facets of information, preparation, and tactics, kudos RuleOfThule), but I have separated them out because my aim is to produce a table of ways to inject dimensions into combat, and I believe each category has its own unique ways to provide that. Squashing the categories simply gives me less clay to work with.

This is by no means an exhaustive or eternal list either; as I am sure many genres exist which feature their own dimensions. A science fiction game, for example, may require multiple people working aboard a single vessel to perform an action or parts of an action. Some kind of “Cooperation” dimension perhaps, or it could simply extend from “Tactics”. Mobility, Range, and Information could be argued to be the most important for decision-making and often are in real-life combat scenarios.

Not all dimensions are equal, and their listing gives my view of their relative important and prevalence in the TTRPG space and rulebooks. Virtually every game includes Attributes, but fewer consider Rewards, Morality, or Disposition to augment combat decisions. Even in games where they do matter, willful negligence or incorrect implementation can lead to them not providing meaningful difference.

Detection in darkness, for example, may have rules but be utterly pointless if everyone can see in the dark; or the ability to remove limits on a powerful ability may transform it from a valuable rarity to the new default action, and thus diminish every dimension that interacted with the old one.

Tables and CHARTS

We have our analysis, but what do we do with it? We make TABLES, of course! We’re RPG gamers after all.

Specifically my goal was to produce tables and theory which I could use for my own games. They are not intended to produce combat encounters from the ground-up, but rather to augment an encounter that already exists; ready to be used. If you have generated an encounter or a room or scene and wonder how you might add choice, add agency, add genuine decisions and discovery for your players to make, that is the intention.

And here is my first attempt at usable material:

Available here:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1cLnK4unp95-v1kGxa34QYl0RIcIilnX2XkocKPWvt7U/edit?usp=sharing

Or as a PDF:

Combat Dimensions

57KB ∙ PDF file

The table requires you make a d12 and d6 roll to decide on a Dimension and an example from that dimension that you might inject into the scene. The intention is that you do this prior to engaging in the counter as part of the prep-work, instead of hot-fixing a fight in progress. As with many random generation tables, the details produced work best when they are woven into the world as a matter of course.

This table works best when the base situation closely resembles our seed fight. Differences such as mindless combatants (undead) or a radically different environment (space, midair, underwater) can result in some results on the table being useless; for that, you’d likely need a tailor-made table factoring in that baseline.

Examples of Use

For an example of how this table might be used:

I have generated an encounter with a group of goblins in a dungeon room. They are of a relatively weaker (Personal Capability) than the player characters, so I wish to make the encounter more interesting. I could simply make them stronger but that would actually diminish the only dimension I have going.

I roll on the above tables and get “4, 4”: “A hungry monster lurks nearby and his hostile to all other sides.” Based on this I could add a slumbering Ogre or Undead into the room. The goblins may be trying to sneak through or avoid its gaze until the players stumble in. If the goblins are smart, perhaps they try to pin the blame on the players or goad the monster into attacking them first.

Another attempt gives me “2, 4”: “The area is unusually enclosed or open, or has adjacent zones.” A flip of the coin tells me it is enclosed. Perhaps the room should be a tight tunnel or cavern that the goblins are adept at moving through, but for which the players have trouble. Their sight lines are obscured and they have to even crawl in places.

A last attempt gives me “8, 1”: “The combatants have laid traps or are aware of traps already placed in the room.” A classic for goblins, they have laid pit traps, arrow traps, or spike traps in preparation for adventurers.

If I were to combine all three dimensions, the area would be a small enclosed tunnel that the goblins have booby trapped against invaders. However, a hungry Carrion Crawler has found its way in and avoided the traps (or perhaps triggered a few to make it weaker) and the goblins are doing their best to keep quiet. Then, the player characters stumble in: trigger traps, piss off the Crawler, and give the goblins a chance for an ambush or to flee.

This gives what I think is a marvelously unique little encounter. It may not be terribly long or complex but its quite likely to be memorable due to all the different aspects combining together. The players have to weigh up the threat from traps, goblins, and the crawler all at the same time, while navigating a tiny space.

Another example:

There is a large Basilisk that has made its lair within a cool sea-side cavern. The Basilisk is a great deal stronger than the players, and naturally has access to poison and petrification abilities. I want to make this encounter more interesting for lower-level characters; allow them to have a chance.

I make my roll and get “11, 1”: “A valuable but fragile reward exists somewhere on the combatant.” From this I could make multiple possibilities:

There is a fragile gem embedded in the Basilisk’s chest that would be worth a great reward, but has a chance of shattering if attacked from the front. The fragments may still be valuable but not as much as the intact gem.

The Basilisk has petrified the princess of a nearby kingdom and uses her as its favorite back-scratcher. They fully believe her to be dead, but if identified and rescued she would bring a king’s reward for the adventurers. However the Basilisk would rather crush her to dust than allow her to be taken.

The Basilisk has gotten its head stuck in a beautiful silver Ogre helmet and is currently trying to free itself. If it succeeds, it will tear the helmet apart, but if slain it will remain intact (save for some claw-marks).

As another example for multiple ways to interpret, I roll “2, 6”: “The combatants have unusual movement (flight, swim, burrow) that they use to maneuver.” An easy one to extend, given the different movement types available.

The Basilisk is semi-aquatic and enjoys swimming. The players may often find it bathing or hunting down fish. It can hold its breath for 6 rounds underwater before needing to re-emerge.

The Basilisk has flight membranes between its legs and a lighter body. It prefers to climb and cling to the ceiling and walls, and dive down upon its prey, then scuttle back up again.

The Basilisk has been cursed and temporarily phases in-and-out of the astral plane, allowing it to essentially teleport. It may be controlled or completely at random.

As a fun addition, during some previews someone tried treating each column of the table as elements of a single combat, to generate it from the group up. Their take on Column 6 was:

An ex-rival/defeated enemy has been forced into service of the current big bad. They have been given pretty rewards but know they are expendable bait that has no choice, and bear the scars of refusing the initial offer and jittery and enraged.

Column 1 as:

A tournament/arena situation with the place having magical items to be used. The non combatants watch gladiator combat and racing, while wizards are messing with them to make it more entertaining spectacle.

And Column 3 as:

A siege/defensive battle; where they are lead by a cunning commander who exploits the terrain and their stockpile of supplies. They might go for allies through a small tunnel nearby after shrinking themselves to fit through.

Wrap-up

If you’ve made it this far, thanks! I appreciate it. I hope this has helped you consider some alternative dimensions for your future games and combat encounters, and given you some useful tools to implement them.

In my reading I found a few examples which seem to touch on a similar concept but none that fully explored it to the degree I was happy with.

“Mastering the Art of Challenging Combat in TTRPGs”

https://man-of-ages.com/2023/12/02/mastering-the-art-of-challenging-combat-in-ttrpgs/

Includes brief examples for personal attributes (resilience), terrain, environments, reinforcements, alternate goals, enemy tactics, and resource management.

“Roleplay in Combat”

https://www.tribality.com/2020/07/21/roleplay-in-combat/

Suggests three principles to give dimensions to combat: character-centered action, using all your tools, and using abilities. Appears to hit on the concepts of Personal Attributes, Abilities, and Morality as dimensions but doesn’t explore them very far.

“TRPG Combat System Design 101: Variables”

https://alannaturner.com/design-blog/trpg-combat-system-design-101-variables

A lone post that covers definitions for individual combat actions in great detail. Outlines actions, initiative, accuracy, potency, cost, range, breadth (area of effect), versatility, duration, and setup (more like impact). Very player-action focused and provides a deeper look into Attributes, Abilities, and Range.

Arbiter of World’s combat system analysis part I and II are also invaluable reads on the subject of design:

I imagine I’ll continue to explore and re-define this concept in the future but already I’ve been fairly satisfied with the results produced, and has unblocked me from some projects I was working on where the combat felt flat. Even a little injection of some different goals, limits, and consequences can be just the thing the brain juices need to start flowing.